In this story taking place in a contemporary village in Zimbabwe the chief, headmaster, and resident healer worry about having enough rain. The resident rainmaker too worries but she is kept from the local rainmaking monument so she must instead rely on her brother the healer and his granddaughter, Chipo, to help prepare the path for a rainmaking ceremony. To cultivate this path, Chipo, gains allegience from an aqueous being (the njuzu) that causes her to figure as a sensitive bellwether of temperature and temperament.

Climate geoengineering advocates have long argued over how to actually define the term "geoengineering."... Click here

Rainmakers' - Christian or Indigenous - Called to Duty Click here

Elsewhere Cited as the "Prior Art" to Thailand's Patented Rainmaking Programme... Click here

This section is for helping you dive deeper into the film and learn more about rainmaking in Zimbabwe.

Rapoko, or zviyo, is an indigenous grain of sub-saharan Africa (Latin, Eleusine coracana). It is germinated through a blessing ceremony by rainmaker (nyusi) in order to make available its’ sugars and nutrients to fermentation in a ceremonial beer - brewed seven days - called msesese. The beer is cooked again in clay pots, over a fire placed near and below the wind vent or “chimney” of a cave during rainmaking ceremonies (chikwa). This substantive and elemental process is part of what welcomes the ancestral spirits in the cave as well as nature spirits, like the mermaid spirit, that may come from outside cave.

In Zimbabwe’s indigenous spiritual cosmology there are ancestral spirits and other kinds of spirits. Among them, is the aqueous being that is called njuzu (Gelfand 1980; Chavunduka 1981; Jacobsen-Widding 2000). In the lore the njuzu is a mermaid that “takes” the artistic or the ill underwater and teaches them herbal medicine and how to create. Before teaching she tests her acolytes - to ensure they have good hearts, manners, and ethics. In the ancient past, however, the njuzu taught differently. Most likely the njuzu was a way of looking and perceiving - as a hybrid of an actual human rainmaker (nyusi) and a non-human who dwelled together in a cave. Caves painted with snake fat and bentonite-red ochre powder throughout Southern Africa depict human figures in mergence with crocodiles, fish and snakes. Oral traditions then confirm that panspecies learning was consecrated in ancient rituals particularly those whereby rainmakers performed altered states as theriomorphic perception (Ranger 1999; Garlake 1960). In more recent times, cave images of mudzimuzangara - ancestral spirit creatures - are repainted before ritual to capture their presence during rainmaking ceremonies.

The njuzu, while called to rainmaking ceremonies today then, may not always or be consistently called to aid in rainmaking in spite of their association with water. Indeed, in general conversation among the Christian or modern-educated sets of Zimbabwe, the njuzu is considered a mere myth. Yet, even newspapers must take the myth seriously when they are cited as the cause for discontinuing the building of dams. Such occasions, bearing deep precedence in the colonial liberation stories of the Nyami Nyami a giant serpent (not unlike the Loch Ness Monster in Scotland) at Victoria Falls, reveal that the myth carries a physical force or resistance that extends beyond mere belief or metaphor.

While no “no evidence of aqueous humanoids exist” declared disturbed oceanographer-members of the US National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Association (NOAA) in 2012 after a Discovery Channel/Animal Planet ’spoof’ aired on television under the pretense that paleoarcheological evidence had been found, the mermaids tale is still one of critical to the ecological heritage and future of life on the planet (see the essay “Where T/here Be Mermaids.PDF).

The grove featured in the film lies adjacent to the National Domboshawa Rainmaking Cave Monument. It is considered a site of ecological heritage itself inasmuch as the grove is constituted solely by indigenous trees. The oral traditions say during colonial times it was meant to be razed for agricultural production but each time they did, the trees hardly budged and where they did they just came back stronger. It is a symbol for indigenous resistance - and is thus called “rambakurimwa” (the grove which cannot be tilled). The flower shown in the foreground at 3:05:09 is no other than the national flower of Zimbabwe - the flame lily (Gloriosa superba).

Kuombera: to give praise, show respect, or call the attention of the spirits, is an embodied spiritual gesture accompanying all Shona relational interactions. It is part of the rhythm of calling out speakers and integrated with speaker’s delivery. In the Shona world, there are also varidzi resango, spirits of the forest whom one must appeal to when accessing non-human entities like plants.

Snuff, or bute, is a fine-ground tobacco sometimes cured with elephant dung. It is kept in ox or cow horn gourds as a special mishonga (magic/medicine) that is appreciated by the ancestors. Indigenous practices call for either the sacrifice of bute in sacred places or the taking of bute sacred occasions requiring the ancestors’ observation or assistance. Nicotine that is easily absorbed into the blood by the fine capillaries of the nose does often cause to the one snuffing it to sneeze. The sneeze is often interpreted as a having gained the presence of the ancestor.

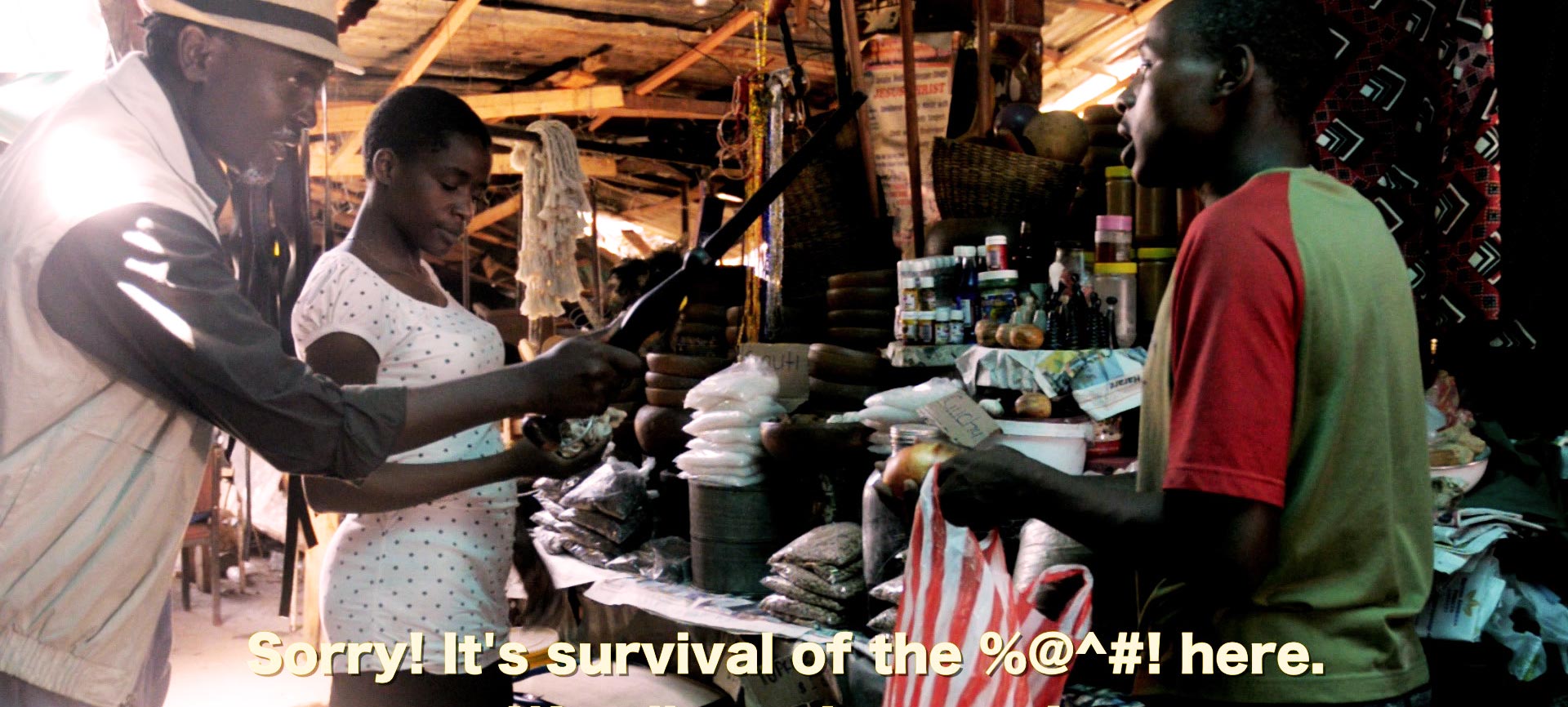

Prior ethnographic research with spirit-mediums, healers, healer assistants, and plant merchants in Zimbabwe has shown the need to recognize the indigenous intellectual rights of most Zimbabwean healing practitioners. While in Zimbabwe there is the Zimbabwe Association of Traditional Healers (ZINATHA) there is also the problem of the public perception of how accessible should be customary healing plants in modern markets (see below). Often, what is known about healing plants is decontextualized from an actual healing practice. Extending Sweetness includes this researched example here to draw a parallel with the character’s concerns for weather, water and ecological health. Meteorological reports predict weather patterns but are hardly derived from the actual engagement with weather patterns i.e. in rainmaking, or water-restoration.

“Protecting Traditional Medicinal Knowledge In Zimbabwe” Author: Chloe Frommer Cultural Survival Quarterly Issue: 27.4 (Winter 2003) Indigenous Education and the Prospects for Cultural Survival

The African Potato (Hypoxis Hemeracallidae) was hot in Zimbabwe in 2000. For years it had appeared in some of the street markets in the capital of Harare alongside other muti, like ginger, as a remedy for stomach aches. Who first began marketing it for its “cure-all” effects cannot be known at this late date because all of the local muti merchants started selling it when they saw its increased popularity with Zimbabweans.

At one point, however, being accountable to no one other than impersonal Zimbabwean consumers, the muti merchants began to display another tuber they also called the African Potato. That potato did not possess any of the active healing ingredients of the original. Accusations of fraud and concerns for public safety followed, forcing the president of the Zimbabwe National Association of Traditional Healers Gordon Chavanduka to appear on national television to distinguish between the bogus potato and the curative African Potato. Although Chavanduka did not reveal the full secret of what the African Potato cured, how to prepare it, or in what dosage it was safe to take it, it was evident to most that the potato he identified as the “real” African Potato was powerful. Hence, as a caveat, Chavanduka had to insist that consumers of the African Potato should always consult a traditional healer for their health needs so they could be assured they were given the right plant.

Tradition Facing Outside Pressures Despite intense interest from pharmaceutical companies, drug legislation agencies, and ethnobotanical sciences in identifying the “right plants” for health and other uses from developing countries, the story of the African Potato reveals that an additional element is significant in preserving biodiversity: identifying the “right individuals” and the “right practices” attached to such plants. In Zimbabwe in particular, individual practitioners provide services based on traditional medicinal knowledge (TMK) of local plants and do not traditionally seek either profit or patent for these medicinal plants’ utility. But because of the weight of international and national agendas that favor novelty and commercial application in intellectual property rights (IPR) legislation, these local individuals may soon be divested of the TMK they maintain and make valuable

Under the jurisdiction of the rainmaker (nyusi) and rain diviner (svikiro remvurua) are human actions considered taboo - both before and during the African Sabbath - which is just before the rainy season (Murimbikwa 2009). As with productivity, the procreative behaviors and states of being (menses, or sex) are restricted. Other “hot” behaviors are also discouraged because they are considered polluting to consciousness. Consciousness should be like a clear stream. So it makes sense that when waters are polluted it is also taboo - the specific act of polluting water at any stage is called either kuwhozhera or kupunjira (Mujuere 2007).

In Extending Sweetness, a tree is taken as a bellwether of how much rain has fallen. This tree is called in Shona mawhute and its’ purple and white fruits whutes. The tree allows percipient action for rainmaking based on two tests: a) the amount of fruits still hanging: if there are plenty the rain has not been sufficient to cause them to drop and b) a stick of the plant delivers an image of the amount of groundwater by the length and darkness of its shadow cast on the ground.

What is interesting about this sensitive indicator, however, is that its’ utility serves to make it sacred for Shona rather than just utilitarian. Of all the indigenous wild fruits that ripen before and into the rainy season, e.g. baobab, majanje, monkey orange etc it is only the whutes which will not be gathered and sold in the markets. Its’ silky texture, neutral flavor and high liquid content means it is not that sweet - hence eaten more for its’ hydrating than its flavor. Moreover, it is the color of the whutes - purple that places it directly between the blue-red color scheme that rainmakers manage throughout the African Sabbath-pre-rainy season. Its’ fruit therefore represent the sense of both hot-cold, red-blue and dry-wet balance that the rainmaker strives for water, cave or wherever ancestors presence is desired. At times too, it facilitates for a divining authority an altered orientation association structure - that allows them to sense specific ancestors in an embodied process called kusvikirwa.

Color, writes Michael Taussig in What Color is The Sacred? is fluid and moving. It is creaturely he argues if we restore its’ ontological being with temperature: “to equate calor (heat) with color detaches us from a visual a approach to vision an makes color the cutting edge of such a shift.” In an indigenous Zimbabwean theory of difference, the constitution of being - or temperament - derives from temperature. This can be discerned from the perception of color. Shona classify and represent things - which are different by their temperature or temperament - in static color states.

For instance, the Shona ceremonial cheera (cloth) designed in a puff adder-ziz zag pattern represents as black or dark blue both ancestors and pregnant rain clouds (hore) which are topped or backgrounded by white - representing precipitation in white, fluffy clouds, and demarcated again from red lightening or fire zigs. The white clouds represents the normal condensation of precipitation as a process mediating between pregnancy/fullness (dark absorbs all colors) and redness (or heat) which is an activating element.

This thermal and fluid paradigm also pertains to perception of what is normal. Rain is seen to generate coolness, coolness generates health and fertility, which generate normalcy and prosperity. The largest contrast is then Drought - which generates heat. Heat generates death and barrenness from which comes abnormality and adversity. So starting from a point of cool water being good to the spectrum made by degrees where hot desiccation is a kind of pollution - we arrive at the Shona cosmological conception of its’ African Sabbath. During the Sabbath just before and slightly into the rainy season, hot, drying and human productive behaviors are anathema. The person who tills his fields before the rain makers perceives it is time for instance can expect their crops to be eaten by baboons because they are out of sync with the overall planning for the rain. Likewise, during the Sabbath rainmakers take care to heal the land with water medicines (mishonga remvura). A site hit by lightening, water polluted or an excessive focus on human or agricultural fertility rather than resting the land, the body, the spirit (kuwhozhera) requires interventions then.

In many cases, the mermaid spirit - represented by blue, white and gold - are called into these ceremonial interventions. This is most likely because the njuzu is also known to be a healing spirit and she takes as acolytes either those who are ‘blue’ with depression or who are morally ‘cool’ in temperament. The colors blue and gold - correspond with the elements of water and light - to make green plants which participate in carbon dioxide exchange in order to process chlorophyll and make themselves sweet. It is said the njuzu likes sweet things and fermented wine as well as eggs. So the njuzu spirit ‘likes’ things perceived to be very pure and elemental. Being an aquatic being too, it notes that the ocean too inhales and exhales carbon dioxide in seasonal cycles that give plant’s breath and shape the atmosphere. So the njuzu also condenses the rainmakers sense of water, light, air as blue, white and gold, and their combinations - as sweet and green.

The film Extending Sweetness is shot outside of the National Domboshawa Rainmaking Cave - a site overseen by the National Museums and Monuments of Zimbabwe (NMMZ) and located 30 kilometers north of the capital of Harare.

The Domboshawa cave, like other caves around sub-Saharan Africa host rock imagery depicting San indigenous spiritual practices. But they are also merge with the indigenous spiritual practices of contemporary Shona living in the area prior to colonisation. The The rock images themselves show theriomorphism and spirit-figures called mudzimuzangara - to be repainted, and re-invoked prior to the rainmaking ceremonies (Ranger 1999; Garlake 1950; Monuments of S. Rhodesia).

However, the politics of heritage are evident in the management and creation of Domboshawa as a national rainmaking monument (see also Breglia 2009; Katsumudanga 2011). Since the NMMZ has taken control of the cave through a one-time opening ritual and subsequently through an adopt-a-site program run by the local school in exchange for the school kid’s free, once-a-year access (Tauravinga 2004) the site is no longer a spiritual shrine. The NMMZ justifies the preservation of the cave in this way and against actual use based on two actions associated with rainmaking: 1) images meant to be repainted may not be repainted otherwise they will look too “new” to be old and not appeal to tourist’s sense of seeing a fossil in time. 2) fires always associated with rainmaking may not be built in the cave, under the chimney, lest they damage the image as well.

While the tangible heritage of Domboshowa and its’ geo-physical formation are preserved mostly for its’ aesthetic heritage, archeologist Murimbika (2009) argues that the “cultural meaning of rainmaking is not limited to the knowledge of the process” (194). Murimbika who explores the rainmaking traditions - based on archeological, archival, and oral evidence of four different regional/linguistic group in Southern Africa - seems to be calling the symbolic, cosmological representation of the technical, indigenous knowledge of rainmaking - mere epiphenomena. The number of variations on meaning exceed the variation on operations. But the ontology of weather, in reality, is no less patterned by cosmology or epistemology, than ecology is effected by human practices and behaviors.

Intangible heritage is then not a superfluous component of tangible heritage. Rather, intangible heritage constitutes the mind of practices and performances with hydrological, geophysical, faunal, meteorological, and floral natures. The patronizing attitude given to these practices is well-rehearsed however in international governmental organizations such the Food and Agricultural Organination which categorizes in documents on its website that all indigenous rainmaking done directly with elements is categorised as ‘magic’ or ‘pseudoscience’.

But the cave monuments’ “wind chimney” - nearly 10 feet high - does permit smoke from the fire (built in the amphitheater below) to reach, undispersed, a high enough altitude in the atmosphere where it can meet with colder cloud vapors, warm them, and then cause condensation to from around the smokes’ tiny particulate until the vapors are ‘full’ enough to rain - right there and then. The hic and nunc nature of the produced effects equate to a situated knowledge that is consistently underlooked by professional meteorological activities - trained mostly in prediction.

The Extending Sweetness film crew chose to contact NMMZ as partners on the film. Our goal was to re-enact the intangible heritage of rainmaking with them as overseers of the rainmaking monument. The NMMZ, on the other hand, was less cordial in spite of being present for meetings. Officers sought to charge the crew to film anywhere near the monument - even though they would not share any geographical guidelines as to the NMMZ’s precise jurisdiction. However, the crew gained clearance and offers of participation from the local chief, local rainmakers, and residents. Eddy K Paraziva (plays the grandfather in the film), also a local land-owner, was our first ‘character of place’ as he had grown up in Domboshawa and played in Rambakurima as a youth. In the director’s first scout of the area - Paraziva showed his extensive herbal knowledge of the place.

Through serendipity our film crew learned that the house with which we filmed - with the blue door - was the home of the present rainmakers - the Chadamoyo clan (the patriarch who plays ‘chief’ in the film). Through our various interactions and friendships with Domboshawa residents several anecdotes were told of local politics that informed both our story and our understanding of the significance of the heritage - tangible and intangible - in the film.

Firstly, locals had been sensitive about the NMMZ’s oversight of their cave and some were resentful of the private business surrounding the cave. The Cave Affair - a resort and restaurant surrounding the monument was one such one and its’ business tended to interrupt and overwhelm community decisions. Secondly, prior to our actual filming a series of murders has been blamed on the customary village rainmaker - sending her roaming before we got to meet her. The story evolved with the idea of a ‘roaming rainmaker’ - played by the aunt of Chipo - then in mind. Thirdly, the question of which religious heritage - Christian, indigenous, or syncretic Christian-indigenous propheta - is most amenable to the national secular policies governing the monument and the practices surrounding it forces cosmopolitical questions into the center of contemporary life.

For this reason our film’s form - docudrama - emerges from the way our research informed the script through which our cast and crew chose to enact the intangible heritage of rainmaking in Domboshowas as it is currently stands and is challenged.